Mae govannen, friends! Josh here with a guest post from Ashlyn McKayla Ohm. A worshiper of the Creator and a wanderer of creation, Ashlyn is most at home where the streetlights die and the pavement ends. She shares poetry and prose dedicated to wonder, nature, and literature on her Substack, Wild Goose Words. If she’s not reading or writing, she’s probably hiking, birdwatching, or otherwise getting lost in the woods.

Today she’s got a fascinating piece for us on a concept found in both Tolkien’s Legendarium and C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy: the “Bent Way.” Intrigued? Read on!

Bridge from the Bent World

by Ashlyn McKayla Ohm

INTRODUCTION

Imagine that you are embarking on a long journey. Your quest will take you across winding rivers, through secretive forests, and over rugged mountains. You’ll encounter cities and cultures both familiar and foreign, and you’ll devote time, energy, and patience to your quest. Yet you will finish transformed—with both a wider view of the world and a more focused perspective of your place in it.

This imaginative journey is an apt metaphor for what it is like to read the seminal work of fiction by J. R. R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion. One of the most brilliant and expansive works of mythology ever written, it is both sweeping and personal, sorrowful and exuberant, richly literary and still accessible. Wandering its copious pages is a journey, indeed—but an enriching and transformative one. This is because The Silmarillion is more than just a chronicle of Tolkien’s fictitious Middle-earth or a glimpse into his profound genius. It is a journey through truth itself, and how the ways that it is heeded—or ignored—shape our destiny. And in classic Tolkien style, The Silmarillion presents this dichotomy as a unique choice between the straight way, or the “bent” one.

This concept, while certainly creative, is not unique to The Silmarillion. It also appears in the writings of Lewis, particularly his Space Trilogy, and finds echoes of itself even in Scripture. Thus, a close examination of this concept will yield not only deeper textual understanding of these writings but also a practical approach for living out our own moments of decision.

THE BENT WAY IN TOLKIEN

To understand the concept of the “bent” path, it’s necessary to look at the Akallabêth of The Silmarillion, which tells of the tragic demise of the once wise and righteous kingdom of Númenor. Engulfed by the fear of death, the rulers of Númenor are bewitched by the evil power of Sauron, who persuades them that the heavenly rulers—the Valar—are keeping immortality from them by forbidding mankind to set foot in the Deathless Lands. Consumed by fear, inflated by pride, and bolstered by Sauron’s lies, the last Númenórean king, Ar-Pharazôn, summons a great fleet to besiege the Deathless Lands and obtain eternal life through violence.

Unsurprisingly, his plan fails. The cataclysmic justice dealt by Ilúvatar—the One—not only destroys Ar-Pharazôn and his army, but also changes the shape of the world so that Númenor drowns in an oceanic rift. His next step is to “cast back the Great Seas west of Middle-earth, and the Empty Lands east of it, and new lands and new seas were made; and the world was diminished, for Valinor and Eressëa were taken from it into the realm of hidden things.”

In other words, the natural and spiritual worlds have been torn apart. And this change is not only devastating; it’s also permanent. “Thus it was that great mariners among them would still search the empty seas, hoping to come upon the Isle of Meneltarma, and there to see a vision of things that were. But they found it not. And those that sailed far came only to the new lands, and found them like to the old lands, and subject to death. And those that sailed furthest set but a girdle about the Earth and returned weary at last to the place of their beginning; and they said, ‘All roads are now bent.’”

Thus, in Tolkien’s universe, the “bentness” of the Earth is not merely topographical but also moral and philosophical. Indeed, in one of the saddest lines of the tale, Tolkien comments, “And there is not now upon Earth any place abiding where the memory of a time without evil is preserved.” In other words, the world has been irrevocably warped. Access to the Deathless Lands—and more importantly, the spiritual powers who reside there—has been cut off. Men are now doomed to endlessly circle the results of their own folly, because the entire creation has taken on the shape of humanity’s sin.

THE BENT WAY IN LEWIS

The reference in The Silmarillion is the introduction to this concept of “bentness.” However, C. S. Lewis, Tolkien’s friend and colleague, also explored this concept in his Space Trilogy, most notably in Out of the Silent Planet, which he was writing during the decades when Tolkien was endlessly reworking the material that would later become The Silmarillion. Whether the two men inspired each other’s treatment of this topic remains unknown, but it certainly appears to have held significance for them both. Lewis, though, took the idea one step further, claiming that it’s not just the cosmos that is “bent” by sin—it’s also human nature itself.

For Lewis, the term “bent” is given first mention in Chapter Eleven of Out of the Silent Planet, when the hrossa—intelligent otter-like extraterrestrial creatures—discover that the space traveler Ransom has not come alone to their planet: “No, he had come with two others of his kind—bad men (‘bent’ men was the nearest hrossian equivalent) who tried to kill him.”

However, as the narrative progresses, we learn that “bent” is far more than a simplistic label applied to moral disconformity. It is a sickness of both deeds and heart—producing not only flawed actions, but a flawed way of inhabiting and interacting with the world. For instance, the hross Hyoi connects bentness to a stubborn negation of goodness, saying, “It is a bent hnau [creature] that would blacken the world.” This cynicism breeds a malevolent cowardice, as Ransom later avers, “Bent creatures are full of fears.”

Yet it’s not until Ransom meets the Oyarsa, or angelic ruler of the planet, that the concept is expounded to its fullest. The Oyarsa explains that humans are “bent” not of their own will, but by the designs of a great enemy—the ultimate Bent One himself. In language obviously meant to evoke the Biblical fall of Satan, he recounts planetary history to Ransom: “Once we knew the Oyarsa of your world—he was brighter and greater than I—and then we did not call it Thulcandra [the “silent planet”]. It is the longest of all stories and the bitterest. He became bent. That was before any life came on your world. Those were the Bent Years of which we still speak in the heavens, when he was not yet bound to Thulcandra but free like us. It was in his mind to spoil other worlds besides his own….We did not leave him so at large for long. There was great war, and we drove him back out of the heavens and bound him in the air of his own world as Maleldil [Jesus] taught us. There doubtless he lies to this hour, and we know no more of that planet: it is silent.”

Thus, when Ransom’s evil captors are brought before the Oyarsa, he is easily able to recognize the proclivities of the old enemy within them. Yet he reacts with more grief than anger at their state: “I see now how the lord of the silent planet has bent you….A bent hnau can do more evil than a broken one.” It is no wonder that, filled with anguish at his new understanding of human nature as well as his firsthand observation of how it impacts this new world, Ransom cries out in despair, “We are all a bent race.”

A BENT RACE—THE PROBLEM

And so, the world is bent—both around us and inside us. Nothing is as it should be, on the macrocosmic or microcosmic scale. We can’t help but share Ransom’s broken sorrow, because we know his words are true: we are all a bent race. And in exploring this concept, Tolkien and Lewis were only taking literature where theology had already gone.

Scripture is replete with warnings regarding pursuing crooked or broken ways. “But as for those who turn aside to their crooked ways, The LORD will lead them away with those who practice injustice” (Psalm 125:5 NASB). Proverbs speaks of those “who abandon the right paths to walk in ways of darkness…whose paths are crooked, and whose ways are devious” (2:13a, 15 CSB). And Scripture agrees with Tolkien and Lewis that this is not a problem humans can fix on their own: “What is crooked cannot be straightened, and what is lacking cannot be counted” (Ecclesiastes 1:15 NASB). Yet like the wise and loving Oyarsa, God still mourns for His people: “They do not know the way of peace, and there is no justice in their tracks; they have made their paths crooked, whoever walks on them does not know peace” (Isaiah 59:8 NASB).

This association of internal corruption with “crookedness” or “bentness” can even be found in medieval Christian writings. While the definition of sin today has primarily narrowed to quantifiable evil actions, for earlier church leaders, as for Tolkien and Lewis, sin was more connected to internal disruption than external manifestation. Theologian Dr. Joel Muddamalle points out that humanity’s broken nature “connects to the concept that Martin Luther and John Calvin popularized in regard to the impact of sin upon our hearts. They used the Latin phrase, ‘homo incurvatus in se’, humanity curved in upon itself.”

This, then, is the curse under which we live. Writer Dave Benson sums up our condition: “There was a time…when all of humanity lived happily and flourished within the form given it by God. But we shut God out and spurned His love. With no definitions from outside, we turned inward and became the silent planet. Now we live in a time—let’s call it bent—when everything has missed its created purpose. It’s not that we’re as bad as we could be; rather, nothing is as good as it should be.”

And yet, as Tolkien and Lewis and theologians throughout history would be the first to assure us, there is still hope.

THE STRAIGHT ROAD—THE SOLUTION

Even in his grief and anger at the way humans destroy themselves, the Oyarsa reassures Ransom about the fate not only of our planet, but of our souls: “We think that Maleldil would not give [Earth] up utterly to the Bent One, and there are stories among us that He has taken strange counsel and dared terrible things, wrestling with the Bent One [there].” And in words that hearken to Númenor’s claustrophobic terror of mortality, he sighs, “The weakest of my people do not fear death. It is the Bent One, the lord of your world, who wastes your lives and befouls them with flying from what you know will overtake you in the end. If you were subjects of Maleldil you would have peace.” In other words, says the Oyarsa, there is another way to live—a way in which the terrible twist in human nature is finally straightened.

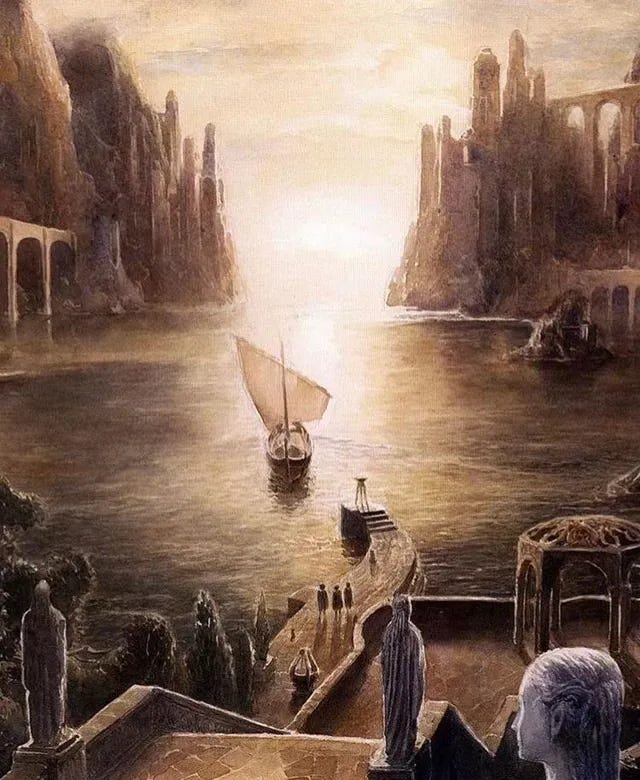

And Tolkien offers the same hope. The drowning of Númenor comes in the terrible final chapters of a book that has recounted great evil—not just from a single act of rebellion, but from the accumulated wickedness of “bent” people for millennia. Yet the book does not close on this dark note. Instead, it glimmers with hope that, in Tolkien’s style, is small, yet surpassingly bright: “Therefore the loremasters of Men said that a Straight Road must still be, for those that were permitted to find it. And they taught that, while the new world fell away, the old road and the path of the memory of the West still went on, as it were a mighty bridge invisible that passed through the air of breath and of flight (which were bent now as the world was bent), and traversed Ilmen which flesh unaided cannot endure, until it came to Tol Eressëa, the Lonely Isle, and maybe even beyond, to Valinor, where the Valar still dwell and watch the unfolding of the story of the world.”

In other words, all is not lost. The spiritual authorities who bore the brunt of mankind’s betrayal and rebellion have still left them one last way to come home. And indeed, the end of The Silmarillion sees Gandalf and the last of the Eldar sailing with Frodo and Bilbo along this road: “In the twilight of autumn [the ship] sailed out of Mithlond, until the seas of the Bent World fell away beneath it, and the winds of the round sky troubled it no more, and borne upon the high airs above the mists of the world it passed into the Ancient West.” As the days of the Eldar upon Middle-earth end, Frodo, Bilbo, and later Sam—prototypes of obedience and righteousness—are invited to accompany them out of the “bent” world in a merciful act of grace.

THE HOPE FOR US

And this “straight road” is the truth and hope for us as well. In the desperate days of the prophet Isaiah, God makes a precious promise to His wayward people: “I will bring the blind by a way they did not know; I will lead them in paths they have not known. I will make darkness light before them, and crooked places straight. These things I will do for them, and not forsake them” (Isaiah 42:16 NKJV). And thousands of years later, John the Baptist quotes this prophecy to show us its wondrous fulfillment—Jesus Himself (Luke 3:5).

Jesus solves the problem of our “bentness” in both Tolkien’s and Lewis’s usages of the word. He comes to a warped world and begins to make “all things new” (Revelation 21:5 NASB), promising to remake the cosmos in its original harmony. And even more importantly, he is bringing His Kingdom to our hearts. Indeed, Lewis considered this to be salvation in its most elemental form: “Each [person], if he seriously turns to God, can have that twist in the central man straightened out again: each is, in the long run, doomed if he will not.”

So yes, Tolkien and Lewis were right. We do live on a silent planet, curved with our own curse. But there is a Straight Way—and He has a name. The God Who said, “I am the way” (John 14:6 NASB) has laid down Himself to be our bridge between this sad, sin-cursed earth and the glory of the deathless lands that await us. Let’s live in the duality of this powerful truth—recognizing our own “bentness,” but rejoicing that the Straight Road has already come.

Hey! Thanks for reading! Did you like this post? Then why not subscribe to Ashlyn's Substack, Wild Goose Words, to get more like it straight to your inbox?Interested in writing a guest piece like the above? Check out my submission guidelines and send me a pitch!

The extended editions of The Lord of the Rings trilogy will return to theaters next month to mark The Fellowship of the Ring’s 25th anniversary! Tickets are available now here: Fathom Entertainment Presents The Lord of the Rings

📚 You can read more of my writing by reading my books! My latest is a collection of essays on The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and more of Tolkien’s works (and their adaptations). You can also find it and more of my books on Amazon or Gumroad

⚔️ If someone forwarded this email to you or you found it through social media or Google, I’d like to invite you to join 15,000+ subscribers in the Jokien with Tolkien community: Subscribe here and get a free gift just for joining!

🏹 Chosen as a Substack Featured Publication in 2023

🪓 Official merch available in the Jokien with Tolkien store

❌ All typos are precisely as intended

🔗 Links may be affiliate, which is a free-to-you way to support this newsletter where I earn a small commission on items you purchase

🗃️ Can’t wait till next week for more content? View the archive

🤝 Want to sponsor a future issue of Jokien with Tolkien? View my rates and packages

So yes, Tolkien and Lewis were right. We do live on a silent planet, curved with our own curse. But there is a Straight Way—and He has a name. The God Who said, “I am the way” (John 14:6 NASB) has laid down Himself to be our bridge between this sad, sin-cursed earth and the glory of the deathless lands that await us.

Beautiful and inspiring!!-- perfect for the start of a new year. Thanks for sharing! 🙏

Great analysis, very thought-provoking. I remember I really liked the way the word "bent" is used both in the Space Trilogy and in the Silmarillion, but I think never made the connection. It is very enriching to think about both Tolkien's and Lewis's concept and relate it to the Scripture!